After knocking around lower Manhattan for a couple years, I began hearing the following declaration. “Oh I never go above 14th Street.” Sometimes the demarcation line was 23rd, or maybe even Houston Street for the truly committed (or terminally cool). This statement was asserted as a point of bohemian pride more than an ironclad geographical rule, or so I assumed. Surely I wasn’t the only downtown resident who ventured uptown for a mercenary 9-5 job (albeit briefly in my case) or the occasional doctor’s appointment. But a certain provincial spirit prevailed and I subscribed too.

Midtown’s sunless corporate canyons resembled, well, not exactly no man’s land, maybe occupied territory? The predictable grid of numbered streets reflected the rigid mindset of the workaday squares occupying all those high-rise office buildings. Of course, for young people of the 1980s who wisely were more concerned with making money and establishing a traditional career, soon to be known as yuppies, Midtown Manhattan was the shining citadel, their means to an end if not the eventual main event.

So it was appropriate that my first break in glossy magazine publishing, my move into the mainstream, landed me in a sleek midtown office tower.

It all happened fast. Overall, the pace of my life accelerated from that magic moment in late 1983 onward. Once again, it began with a phone call.

One desultory evening in October, David Fricke contacted me about applying for a job at a music magazine start-up he was involved with. I knew his byline from Rolling Stone and Musician, but we had never met.

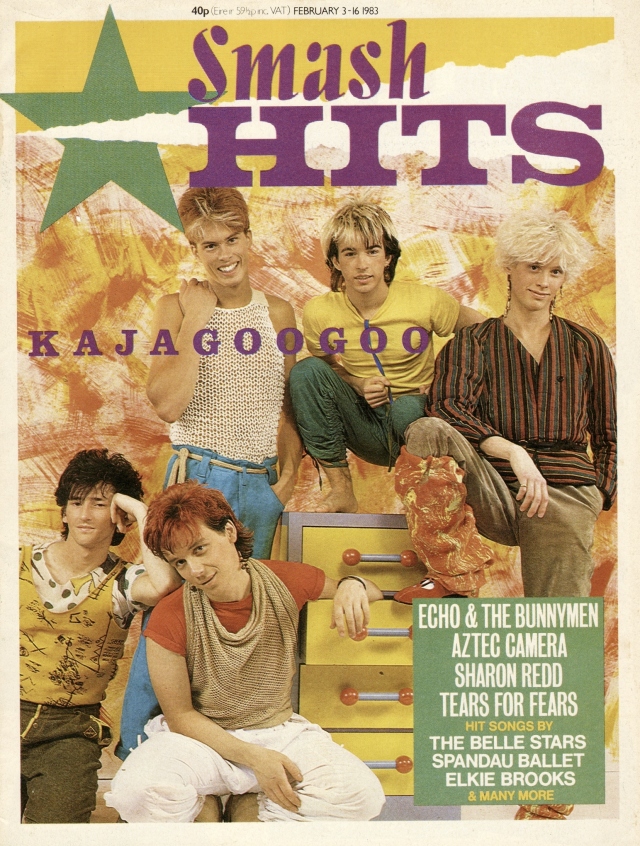

Smash Hits was at that time the best-selling music publication in the UK though it was almost impossible to obtain in the States. Hence the need for an American edition, though due to legal conflict it would be saddled with the ungainly title Star Hits. In those days I monitored the UK scene by reading the weekly New Musical Express; until Fricke phoned I’d never heard of Smash Hits. There was a resistance, verging on hostility, among many American journalists toward English groups. When I wrote about New Order and Joy Division in The Village Voice at the beginning of 1983, most writers in my circle were incredulous. “How can you stand that shit?”

But it turned out I was familiar with the musicians covered in Smash Hits. And thanks to MTV’s explosive growth over the preceding two years, so were millions of young Americans. While the so-called New Romantic movement came and went on our soil, its hyper-stylized standard-bearers like Spandau Ballet and Duran Duran had apparently soldiered on back at home. And their videos — especially Duran’s lavishly produced and ludicrously “plotted” travelogue clips — had become staples of the new music video channel in the States. Which meant teenage mall denizens across the country were hearing more new music than the self-styled tastemakers in the big city (like yours truly) might have ever imagined.

Signs of an impeding breakthrough surfaced throughout 1982 and ’83. Synth-friendly English groups like Human League and Soft Cell, who were also not averse to the increasingly tech-driven rhythms of contemporary black music, began to be heard on the playlists of downtown dance clubs and urban radio stations alike. When Culture Club reached Number 2 on the Billboard pop charts with the gently soulful Motown appropriation “Do You Really Want to Hurt Me” in late 1982, there was no turning back.

As pleasant as Boy George’s sweet Smokey-derived voice sounded, and still sounds, actual music accounts for only half of Culture Club’s appeal if even that. Androgynous performers were absolutely nothing new in pop music yet the former George O’Dowd brought something unique to his gender-bending persona. Boy George decked himself out in outrageous makeup and natty dreadlocks while simultaneously projecting a cuddly, non-threatening, nearly asexual vibe — a drag queen you could bring home to meet Mom. Or hang his poster image on your bedroom wall without her freaking out.

Revealingly, Culture Club’s videos were nowhere near as sophisticated or well-made as Duran Duran’s, as British journalist Dave Rimmer indicates in his indispensable study Like Punk Never Happened. Nevertheless Boy George’s perversely wholesome charm and penchant for camp proved to be irresistible to American audiences. For awhile. In the wake of Michael Jackson’s soaraway success, pop visuals suddenly mattered more than ever before, perhaps even more than the music itself.

Even Rolling Stone, then as now the house organ of traditional rock culture, deigned to address the coming sea change with a Culture Club cover story; Boy George (alone) fronted the November 10, 1983 issue, in all his finery.

“Something was definitely happening, “ wrote Kurt Loder. “We turned on the radio, and white-boy black rhythms boomed from the speakers. We went for our MTV, and there were dozens of dandies parading across the screen. We danced at the clubs and noticed it was getting hard to tell the boys from the girls, the girls from the boys, and no one seemed to mind. A trend, perhaps. A new British Invasion. Indeed, the American charts now list more records by U.K. acts than at the height of Beatlemania, nearly twenty years ago.”

With an interview scheduled less than a week after David Fricke’s phone call, I had to scramble on the requested writing samples. I chose two reviews of British groups, the aforementioned New Order epic and a shorter look at Eurythmics’s debut album Sweet Dreams. In addition I’d been asked to compose brief takes on two current singles: David Bowie’s “Modern Love” and Eurythmics’ “Here Comes The Rain Again”. Luckily, I liked both quite a bit despite (or because of) their presumed commerciality. The magazine was going to be called Star Hits for a reason, right?

On the designated day, I hopped the E train to 53rd Street and then walked up Lexington Avenue to East 58th Street. Though the office of Pilot Communications was only a half-dozen or so blocks away from where I’d worked at Video Marketing Newsletter for six months in 1982, the parent company of Star Hits proved to be situated in another world entirely.

Bloomingdales, the fabulously upscale department store, defined this bustling neighborhood. Alexander’s, a slightly downscale department store roughly comparable to Macy’s, sat directly across the street from my destination. I regarded this area as “the retail district” and never came up. May’s on 14th Street, if worse for wear, was closer and more affordable.

Though it wasn’t yet noon the sidewalks were already packed with suburbanite ladies toting hefty shopping bags amid a better-groomed breed of beggars and street hustlers than you’d see in Times Square. On the corner of 58th and Lexington, before I turned right, an incongruous figure stood behind a table. Her stentorian voice drowned out the traffic noise.

“SIGN THE PETITION! FIGHT BAAAAACK WOMEN!

Passing close by her pulpit I saw why people steered clear. Hanging from the table was a gruesome poster, reproduced from Hustler magazine: a naked female body being fed into a meat grinder, under a doctored caption reading “STOP PORN.”

The feminist protester was a gaunt thirty-something redhead with freckles and a confrontational stare. Between her ascetic crew cut, faded army-surplus pants and combat boots, she resembled a lesbian graduate student who’d scolded me for playing The Rolling Stones’ “Stupid Girl” at the record store where I’d worked during college in Ann Arbor. Dubbing her “the anti-porn lady”, in the interest of diplomacy I opted not to sign the petition. I never suspected that witnessing her lonely crusade would become part of my daily routine.

After entering the wrong side of the building I was grudgingly redirected by security and gradually made my way to an office suite on the 20-something floor. Riding the elevator, I observed a gamine adolescent who vaguely resembled Brooke Shields listening with bowed head while a middle-aged woman (obviously Mom) hissed inaudible instructions. When they disembarked on a floor in the teens, I glimpsed a sign reading “Elite Models Youth Division.” This too would soon become familiar.

Star Hits headquarters consisted of four or five rooms opening into a reception area barely big enough to contain the receptionist’s desk and visitor’s couch. At this juncture, Pilot Communications was a startup business, not successful enough (yet) to require (or support) a full-time receptionist. Susan Freeman, who occupied that desk on my first visit, also served the company as production editor, office manager and right-hand woman to the CEO. And since Felix Dennis split his time between New York and London, Susan was often left in charge.

With her prematurely grey Jewish-Afro hairstyle and piercing vocal timbre, Susan Freeman was a presence. She greeted me effusively.

“Oh you must be MARK COLEMAN.”

Ushered by Susan into the compact editorial sanctum, I quickly took in the sweeping city view through the picture windows and met the co-editors. They couldn’t have been more different, in terms of physical appearance. David Fricke was imposingly tall, well over six feet and slender, sporting shoulder-length hair and blue jeans, quiet of demeanor yet displaying quick, lively eyes behind light-sensitive wire-rimmed glasses. Neil Tennant, on extended loan from Smash Hits’ London office, registered as more outgoing in our initial encounter: effortlessly articulate, succinctly describing the magazine’s mission while flashing the occasional sparkling glance of amusement or sardonic raised eyebrow. Neil was medium height and build, with slightly curly and neatly shorn brown hair. Though at that point I rarely noticed clothes on women or men, I remember he wore a striking collared shirt and shiny black leather shoes with his Levis. Impressed by both men, I decided minutes into the interview that I would do anything to get hired.

Somehow I fronted my way through the interview with revealing my ignorance of the magazine itself. Or maybe they knew? Still they praised my test assignment and gave me a few copies of Smash Hits to take home. When they said, “we’ll be in touch”, I tried hard to hide my enthusiasm.

Reading the magazine for the first time back downtown in my 9th Avenue cavern, I totally lost my shit. Smash Hits really was a teen mag, with screaming girls and everything. However, when I read Neil Tennant ’s cover story on Kajagoogoo (one-hit wonders of “Too Shy” infamy) in the May 26 1983 issue, and read it again, and again, I finally saw the light. Another road to Damascus moment. The story was, in the breathless parlance of the time, brilliant: witty, sharp and observant.

I was a mildly fierce critic of the group myself until it began to dawn on me that, if they were criticized so widely and so frequently, they must be doing something right.

Instead of gushing or condescending or pandering, Neil and Smash Hits gave their young readers a sense of what the pop-star subjects were like as people – plus a peek behind the Wizard of Oz music-biz curtain.

At first, I was hired as a freelance writer/editor, though “freelance” translated into Neil or David calling almost daily. “Are you busy?” “Uh, NO.” I was between jobs and scraping by on writing assignments. “Why don’t you come up and give us a hand.” New Pop and Star Hits were a godsend. Next stop: 1984 and something resembling World Domination.