Our education was based on euphemism, attenuation and accommodation.

— Edoardo Albinati, The Catholic School.

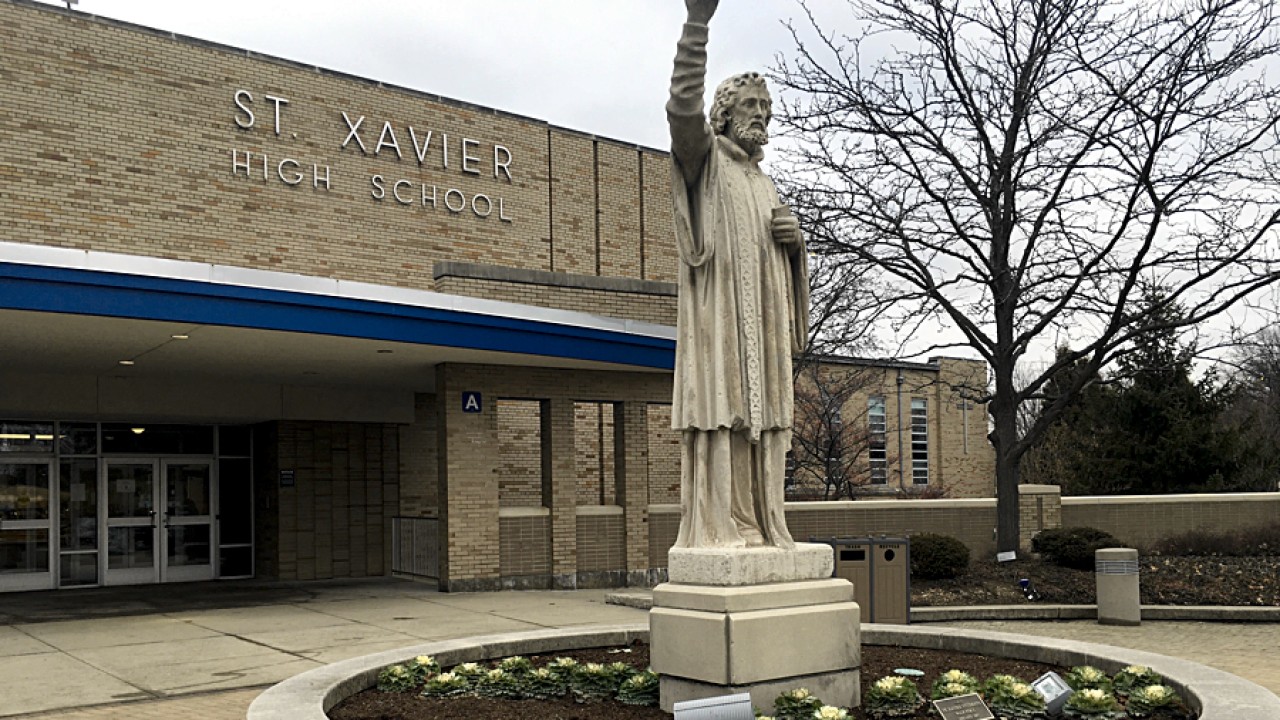

The peak of my academic career at St. Xavier occurred early on, two or three weeks into freshman year. Our first English assignment was an essay on Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn. Before handing back the graded papers, “Mr. Doral” (about half the teachers at St. X were laypeople, including two women) announced that he would read one exceptional effort aloud. Two sentences in, I registered first shock and then pure pleasure — the pride of recognition. (I wouldn’t feel this thrill again until, decades later, my son was introduced as the top-ranked student at his high school graduation.) My essay positioned the slave Jim as a better role model to Huck Finn, and a far wiser man, than any of the novel’s white authority figures. Soon but not soon enough, I gathered this obvious interpretation, not to mention the deep well of skepticism from which it sprang, would not be shared or countenanced by the vast majority of my instructors. Also, this was the first and last time during four years of high school that my nascent writing ability was recognized or acknowledged in any way.

***

Absorbed by twice-daily swimming practice plus homework, I barely registered the absence of women during freshman year. But the stultifying aroma of an all-male atmosphere seeped into my pores, spreading until it turned my stomach. In the spring of 1973, St. Xavier won the Ohio state swimming championship. In a school-wide PA announcement, I was acknowledged as a member of the winning 4 x 100 yard freestyle relay team and the only freshman on the varsity squad. Much to my confusion, right after this recognition crackled through the loudspeaker located next to the clock, our Spanish teacher sneered and mocked my achievement — out loud, in front of everybody. I neither expected nor desired an “atta boy” pat on the back. Yet it took a minute to comprehend why “Mr. Bilgerman” (also head baseball coach) was so contemptuous.

Swimming was widely regarded as a less-than-manly pursuit by participants in the “ball sports.” And Bilgerman’s baseball squads, as well as St. Xavier’s football and basketball teams for that matter, traditionally had never ranked high in the city league, let alone triumphed on the state level. All right then, he was jealous. Still, his unexpected and humiliating insult in the classroom seriously deflated my ego. He planted a seed of doubt, a sense of difference, in my developing self-awareness. There was a masculine standard, unspoken but understood, that I would never meet.

***

Forcing people to act contrary to their own natures is the ultimate proof of power. —ibid.

***

My extracurricular interests – science fiction, Kerouac’s On The Road, New Journalism, rock and roll above all else – bobbed up to the surface during sophomore year. I read and re-read Tom Wolfe’s Electric Kool Aid Acid Test. What attracted me to the story of Ken Kesey and his Merry Pranksters was not only the drug experimentation and psychedelic music, but also Wolfe’s flashy, shape-shifting descriptive prose coupled with observant reporting. Around this time I encountered the rock critic Lester Bangs at the public library, writing about exotic creatures such as Lou Reed and Iggy Pop in Stereo Review. And at home I’d become mesmerized by Pauline Kael’s movie reviews in my parents’ copies of The New Yorker.

In English we studied poetry and drama while drilling vocabulary for the SAT test the following year. Two more formative sophomore memories: reading Sophocles’ Antigone between heats at a spring swimming meet, and voluntarily memorizing Shakespeare’s Sonnet 73. I was far from a gloomy death-obsessed teenager, yet the Bard’s wintry imagery struck me then, and strikes me now, as incomparably haunting and beautiful.

That time of year thou mayst in me behold

When yellow leaves, or none, or few, do hang

Upon those boughs which shake against the cold,

Bare ruin’d choirs, where late the sweet birds sang.

In history class that year, we read The Autobiography of Malcolm X. How on earth did that happen at conservative, 99% white St Xavier? While I can’t recall any accompanying discussion or explication, Malcolm’s clear-eyed tales of his (pre-conversion) ghetto wild life stayed with me forever.

Before or after Easter 1974, in lieu of a Spring Break, St. Xavier High School uncharacteristically decided to broaden the curriculum (and our growing minds) with a period of extracurricular programming devoted to “The Arts.”

Predictably, it did not end well. A screening of The Heart Is A Lonely Hunter with Alan Arkin got interrupted just minutes into the movie, by a snickering student in the peanut gallery. The film was abruptly terminated and so was Arts Week. In the following years, we stuck to our regular pre-Easter program of study days, mid-term exams and a brief vacation.

Nobody else cared about finishing the movie, or Arts Week. My fellow students were mostly pissed about having to resume our routine. A few years later, however, I caught The Heart Is A Lonely Hunter at a campus film group; by then it seemed overwrought and corny, but gaining “closure” was satisfying.

Long after I graduated, my father pointed out a guiding principle of my high school that was so obvious that I’d never noticed, or just took it for granted: St. X emphasized math and science at the expense of every other subject save religion. This was practical in the short term, but tragically short-sighted in my dad’s view, which was interesting coming from a chemical engineer and industrial salesman. As evidence, for two consecutive years at St. Xavier my history class consisted of a varsity athletic coach talking (and joking) about his World War II experience — every day. It wasn’t until college that I realized the liberal arts and social sciences were regarded as serious academic disciplines in the real world.