Inside Story: A Novel finds 70 year old Martin Amis in reflective mode

If any author is amply qualified to write an autobiographical novel, what is now referred to as “auto fiction,” that writer has to be Martin Amis. In a sense he was born to it. Writing fiction was for all intents and purposes the family business; with nearly 40 novels between them, plus assorted short stories and nonfiction, Martin and his father Kingsley (1922-1995) comprise the most accomplished (and perhaps only) father-and-son team in English literature. You want meta? Art and life commingling? Not only does Martin Amis himself briefly appear in his breakthrough novel Money (1984), when Kingsley encountered his son’s name in those pages, he hurled the volume across the room and never retrieved it.

In his memoir Experience (2000), Martin Amis examines his relationship with Kingsley (a mega-eccentric yet loving dad) in an often funny and ultimately moving series of scenes and anecdotes. In between he wrestles with a mid-life crisis mediated by the tabloid press and discovers that his first cousin, missing for decades, was the victim of a serial killer. What he only alludes to, presumably out of respect and discretion, is the breakup of his first marriage. Kingsley, on the other hand, sounds a pithy note when he reflects (in his Letters) on the breakup of his second marriage.

“Well, it’s all experience though it’s a pity there had to be so much of it.”

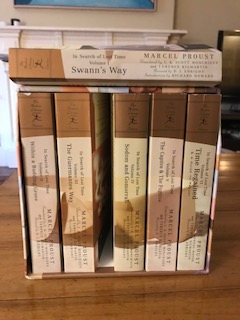

Twenty years on, Inside Story finds Martin Amis all the more experienced in the grim rituals and grinding inevitability of aging, loss and acceptance. And it’s no roman a clef. This time, for the most part, he names names: Journalist Christopher Hitchens (best friend), Nobel Prize winning author Saul Bellow (mentor), poet Philip Larkin (close family friend). The all-star cast inspires Amis’ most ardent and empathetic writing to date, with his verbal dexterity and killer-instinct wit fully intact.

During the Eighties, Martin Amis deflated blowhard masculinity in the aforementioned Money, and London Fields. From Money:

I hit a topless bar on Forty-Fourth. Ever check out one of those joints? I always expected some kind of mob frat house policed by half-clad chambermaids. It isn’t like that. They just have a few chicks in knickers dancing on a ramp behind the bar: you sit there while they strut their stuff. I kept the whiskies coming at $3.50 a pop, and sluiced the liquor around my upper west side. I also pressed the cold glass against my writhing cheek. This helps or seems to. It soothes.

Money‘s loutish narrator John Self did more to undermine the Time Square porn scene than Mayor Rudy Giuliani and generations of crusading clean-it-up reformers.

Martin Amis moved past these darkly comic novels onto more “serious” subjects (nuclear weapons, Nazi death camps, Stalin) in the Nineties and beyond, receiving widely mixed reviews for his efforts. In The Pregnant Widow (2010), he returned to his own history, re-examining the sexual escapades of the Seventies albeit from a far loftier perch than his down and dirty report-from-the-front Dead Babies (1978). Reading The Pregnant Widow as a freshly minted man of 52, I was flattened by this introduction.

As the fiftieth birthday approaches, you get the sense that your life is thinning out, and will continue to thin out, until it thins out into nothingness. And you sometimes say to yourself: that went a bit quick. In certain moods you may want to put it a bit more forcefully. As in: OY! THAT went a BIT FUCKING QUICK!!!…Then fifty comes and goes, and fifty one, and fifty two, and life thickens out again. Because there is an enormous and unsuspected presence within your being, like an undiscovered continent. This is the past.

Elsewhere in The Pregnant Widow, Amis recommends middle-age men reckon with their romantic past. In his case, well into middle age, at the heart of his new novel, past romance resurfaces in the character of Phoebe Phelps, and she’s nearly too much to reckon with. This is where Inside Story becomes traditionally fictional, though the author has suggested the irascible Ms Phelps is a composite of former real-life lovers. In any event, she’s a handful.

As a longtime fan of Martin Amis, I’ll argue that Inside Story is his best book. Whether or not one feels it fulfills the subtitle A Novel. But I’ll also admit that having read all his books may be necessary to feel this way, and it surely enriches the experience. To wit: when the dying Hitch announces from his hospital bed that he must segue to the “rethink parlor” or the brazen Phoebe describes how Philip Larkin will be able to retrospectively “structure a wank” around their encounter, both turns of phrase cf. Money, the Martin Amis oeuvre has satisfyingly come full circle. And when his wife Isabel Fonseca (called Elena in the book) consoles Martin after the disturbing reappearance of Phoebe late in his life, Inside Story offers something resembling optimism for the future.

“‘Well, if you do go crazy, I’ll stand by you. Up to a point.’ This is eminently reasonable, and loving. Probably the most one could expect, or hope for.”