At the end of my sophomore year of high school, our varsity swimming coach, let’s call him Danny Black, switched roles with the reserve (junior varsity) coach. The new head coach, who we’ll call Nick Plato, was far from a popular choice among the athletes. The contrast between the two was stark, dramatic. Mr. Black was a mellow overseer who corralled talent and then, in effect, let us train ourselves; he rode the team with the loosest of reins. Mr. Plato, alternately, was a whip-cracking motivator as well as (though these terms had yet to enter the vernacular) an obsessive micro-manager and control freak. He was a bodybuilder, too: bulked biceps and ripped pecs strained against his shirt seams. He spoke in a pinched, precise tone. Hearing Senator Ted Cruz (R-Texas) declaim on television in the 21st Century eerily reminds me of “Big Nick” Plato’s voice. We never dared call Mr Plato “Big Nick” to his face.

This dizzying upside-down coaching turnover went public at a team meeting, just before the first day of training in fall 1973. The autumn ritual of resuming daily swim practice always hung over our heads and this time, it fell swift and hard.

***

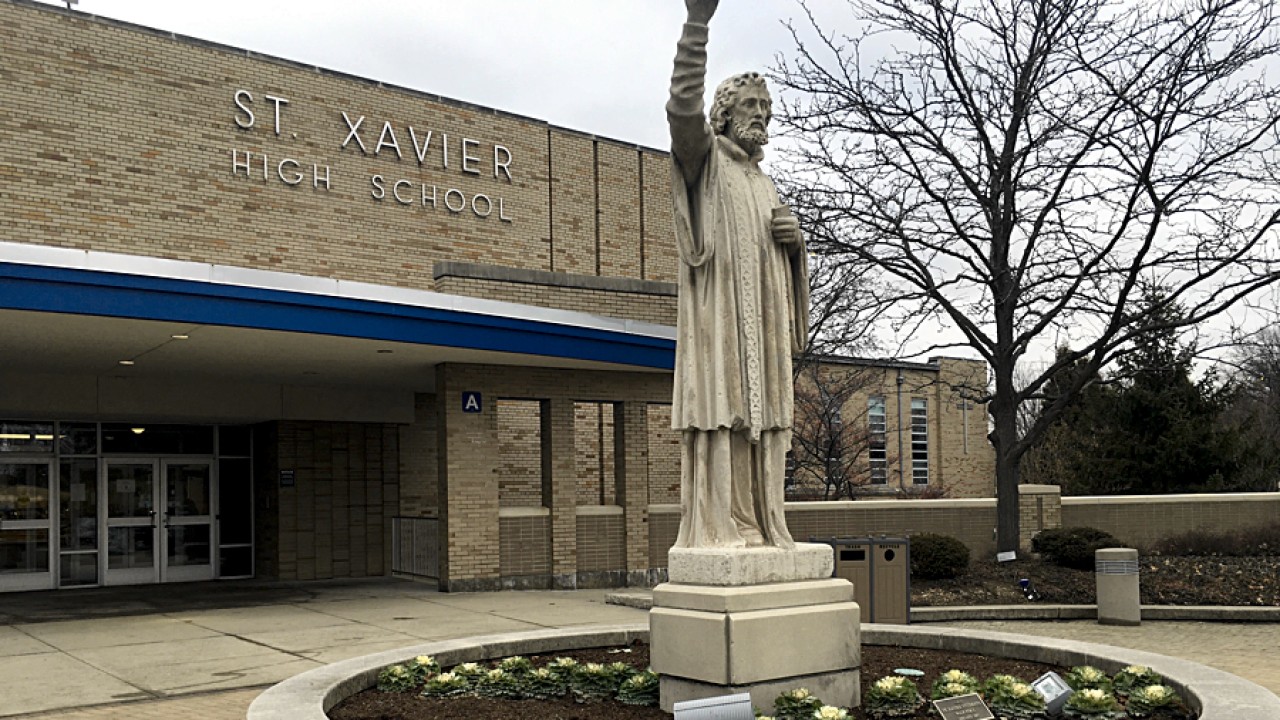

Religion is a mandatory subject at every Catholic high school, and the Jesuits — that most intellectual of religious orders — at St. Xavier prided themselves on reaching beyond rote catechism, in the hope of providing us with a rigorous, complex and logical basis for our faith. Freshman year our religious instructor was a Scholastic (post collegiate Jesuit-in-training) named Milton Parker who we addressed not as Father or Brother but Mister Parker. I can’t recall much of anything about that first year of thoughtful religious indoctrination other than Mr. Parker, who wore his brown hair long, Jesus length if you prefer, tied back in a ponytail. He also led an after-school group of students entranced by the then-trendy Charismatic movement; they stoically suffered as their skeptical peers hurled the nickname “Jesus Freaks” at them. A year or so later these Jesus Freaks, and Mr. Parker, had abruptly faded from the scene, ascending to the next step of their respective journeys. Recently, perusing a conservative Catholic website, I noticed a Father Milton Parker (grey, sans ponytail) advocating a harsh stance on Francis, the current (Jesuit, liberal) pope.

Father Edmund Priggen presided over our sophomore religion instruction. He was a short, slender, deceptively quiet man with greying temples and the nasal drawl of a native Cincinnatian. Father Priggen exercised his moral authority outside the classroom as well as inside. Serving as lunchroom proctor, he specialized in silently hovering behind the tables, trawling for any incriminating and/or embarrassing banter. “Ah Mr. Coleman, that sounds interesting,” he’d interject. “Please continue.” Most students seemed to respect him, or tolerated his eavesdropping. I thought his entire schtick was creepy.

***

Our high school teachers — priests and lay people alike — addressed us students by our surnames, often preceded by a sarcastic Mister. The nuns in elementary school took the opposite tack: both in compassion and (more often) in correction, in condemnation, in perpetual disappointment, they referred to us by our given names. In high school, we followed our teachers’ example; I have a lifelong friend from that era who still calls me Coleman. Now I hear him with great affection, though back then I bristled at our instructors’ insistent use of surnames, as they surely intended. As with so many things, it was meant to “toughen us up.”

***

Traditionally the Sacrament of Confession occurs in a confessional booth with a screen separating priest (confessor) and sinner (confessee). Before receiving First Communion in second grade, we were initiated into this uniquely Roman Catholic ritual, purifying our young souls for the host. Mrs. Davis, our stern teacher, assured us of the absolute anonymity of the confessional: Father Ratterman, St. Vivian’s pastor, would have no idea whose sins he was absolving. Before that happened, we practiced. Mrs. Davis assumed the priest’s position in the booth and conducted a dry run. “Make up a sin and I’ll forgive you, and don’t forget when you confess for real, Father won’t know who you are.” When my turn came, I knelt and blurted out that I’d robbed a bank. “MARK COLEMAN that’s not funny!”

During sophomore year in high school we were compelled to enact the sacrament of confession outside of the confessional, in a casual setting i.e. face-to-face with our religion teacher. For me, this ritual had always elicited an empty recitation of half-invented infractions, even behind the screen. So facing the always-inquisitive Father Priggen wasn’t as awkward as it might’ve been since I had zero intention of owning up to anything concrete. During this so-called confession, or perhaps a subsequent “counseling” session, Father Priggen carefully asked if I had “problems with masturbation.” I replied “maybe at first but now I’ve figured it out.” If he didn’t already, after that he considered me “snotty” — a lost cause. And I never again confessed my sins, well, not to a Catholic priest anyway.

***

True machismo cannot be anything but intrinsically homosexual.

— Eduardo Albinati, The Catholic School

***

“Fag” was the insult du jour among students at St. Xavier during my time there though for the majority of us, homosexuality was an utterly alien concept. It’s not as though there were many openly gay men (or women) living in Cincinnati during the Seventies. Possibly a courageous few in the bohemian districts of Clifton and Mt. Adams, but the overall vibe was repressive, and repressed. Around this time I recall reading, and not really comprehending, a news item in The Cincinnati Enquirer about a police sting operation in a department store restroom. Included in the article were the names and addresses of the men arrested for homosexual solicitation.

When the priest molestation scandal first reared it ugly head in the media, around the late Nineties, I called my younger brother (who graduated from St. Xavier in 1980) and asked if he suspected that any of the priests who taught us had been engaged in sexual abuse. Between the two of us we drew a blank; nobody obvious came to mind.

***

Growing up gay in conservative Cincinnati during the Seventies must haven been a challenge. Growing up gay and attending Catholic school in conservative Cincinnati during the Seventies taxes my limited imagination. But I believe, deep in my soul, that human beings are remarkably resilient.

***

A decade after high school, I worked, and became good friends with, a gay man who leaned toward camp flamboyance in his self-presentation. We lived in Manhattan, after all — it was no big deal. I relished his outrageous sense of humor, even as he regaled me with ironically “juicy” stories until I protested “too much information, David.” One morning as we sipped coffee at our desks he brought up a porno video he’d screened the night before. “It was about a coach who seduced his male swimmers, hahaha, did that ever happen to you, Mark?” “Good Lord, no way!” I laughed and shrugged it off. But at the same time, a lightbulb switched on overhead and stayed dimly illuminated. Not to me, but maybe to somebody else?

***

I peaked early in high school (which is not the same as peaking in high school). If only I could’ve graduated after junior year, my swimming career might be judged a triumph. St. Xavier won the state championship in 1975. A second-place finish in the 200 yard freestyle (clocking at 1:43) qualified me for honorable mention All American. But my academic status was less impressive. The pattern of elementary school continued; I scored high on the SAT, though my grade point average hovered near (or below) B-. At the best of times I was inconsistent, and the St.X emphasis on math and physical science made a poor match with my skill set.

But that combination of high test scores and top rankings in the pool cast me as a strong candidate for college recruiters, especially since many gifted athletes are indifferent (or worse) students. Often this isn’t due to low intelligence, not at all; any sport becomes a demanding full-time job once you vault the basic hurdles and begin to experience success. The hours spent underwater, both before and after school, often left me exhausted by lunchtime. But that’s no excuse for not studying.

***

The new coaching regime effected one startling development. In an unprecedented move, alongside his pledge of zealously enforced zero-tolerance training rules on smoking and drinking, Mr. Plato organized a group of female cheerleader/timekeepers. Mostly recruited from the local all-girl Catholic schools and including several swimmers’ siblings, this distaff squad was awkwardly dubbed (by Mr. Plato) the Aqua Maids.

Their official attire was uniformly prim; white blouses and knee-length blue skirts, not dissimilar to the actual uniforms they wore at Catholic school. Much later, I realized the Aqua Maids received the far better end of this bargain: they were sanctioned to spend time watching guys in Speedos.

A healthy number of dates and assignations, of varying endurance and intensity, occurred between swimmers and Aqua Maids outside the pool confines. But as far as I was concerned, their true function – an invaluable contribution to team spirit and my personal state of mind – was disrupting the all-male monotony of our daily lives. Truly, they were good Catholic girls.

In retrospect I’m convinced that the gender segregation of Catholic high school stunted my social development. Arriving at a large public university in September 1976, I realized that my Jesuit education put me ahead of my fellow freshman in schoolwork, and put me at a disadvantage on the social scene. And it wasn’t purely sexual; on a day-to-day basis I felt stilted, nervous around women. I couldn’t relate to them as peers, friends, classmates or co-workers. My comfort level and confidence improved over the ensuing four years, but I started off with a disability.

Junior year of high school kicked off with another notable shift: our religion class turned toward more self-consciously cerebral investigations. Naturally, sex was at the center of our 16 and 17 year old minds, and our teachers were well apprised of that reality. My religion teacher that year was Father Paul Dorger, a handsome and charismatic man of early middle age who at times seemed too easy-going, too much of a hale-fellow-well-met, to be an effective priest. But he deployed his charm in service of The Faith, without coming on as a phony or flake. He was sincere and self-aware in equal measures; he knew better than to patronize or bullshit his students.

During the second semester, I submitted an essay exam that perfectly regurgitated the content of Father Dorger’s preceding lectures with an accompanying disclaimer: “The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect those of the student.” He gave me an A+ for that paper, and the semester. It was the highest grade I received at St. Xavier. Unlike many of his brethren, Father Dorger possessed a fine sense of humor.

But with all due respect, this good Father, easily my favorite high school teacher, might’ve benefitted from a more finely-honed sense of irony. He wasted an inordinate amount of time – any would’ve been too much – having us read, and then listen to him debunk, Hugh Hefner’s self-justifying Playboy Philosophy from the early Sixties. We may have been the only people not employed by the magazine who studied Hef’s silly treatise. Earnest Father Dorger didn’t get it. The old cliche was true (unless you were a writer): Playboy primarily existed for the pictures.

The Ohio State Swimming Championships were held in mid-March at the Ohio State University pool. Swimmers competed in Sectional and then Regional Meets, with the top finishers qualifying for the State Meet. The event in Columbus occurred over two days, with preliminaries on Friday yielding a final six swimmers in each event. The St. Xavier squad stayed in a motel near the Ohio State campus. In 1975, I qualified for the finals in 200 yard Freestyle as well as the four-man 4 X 100 yard Freestyle Relay.

Pre-race jitters ruled during the State Meet. Never a consistent sleeper even in the off-season, I tossed and turned all night leading up to any major swim competition. In 1975, Coach Plato suggested a novel means of “psyching up” his qualifying swimmers on the night before finals. He offered to hypnotize us. I figured why not? It might help me settle down and get some rest. My best friend on the team speculated that Nick Plato’s motivation stemmed from his authoritarian impulses: this so-called hypnosis was a ruse for extracting damning admissions about smoking pot and drinking beer (in which we both occasionally indulged). My buddy flat-out refused to participate. Maybe I should’ve followed his example.

Nothing untoward happened. No confessions were extracted. In fact I was unable to “go under” and Mr. Plato ended the session when it was clear I wasn’t in a trance, at least not in any more of a trance than usual.

But this aborted experiment was one I never forgot. Or more accurately, it was a confused, and confusing experience that I filed away until it resurfaced years later — when it started to make some sense.

The attempted hypnosis took place in a darkened motel room, lit by a candle or single bulb, with only the coach/hypnotist and one swimmer at a time present. As a mental rehearsal or reinforcement, we were instructed to lay on the bed wearing just a bathing suit. And not merely a Speedo, but an even-skimpier Lycra “speed suit” that was saved for the season finale. Another one of our year-end rituals, a speed-enhancing aquatic trick that sounds suggestively homoerotic only in retrospect, was “shaving down”: removing all body hair (not much in my case) to eliminate drag in the water.

I closed my eyes and concentrated on whatever words the coach intoned to lull me into a suggestive state. But no dice. After ten or fifteen minutes, he threw in the towel (so to speak) and I sat up. What freaked me out was the look on Mr. Plato’s face. He looked distraught and startled, as if I’d caught him off guard. Almost guilty. I had absolutely no clue how to process this expression of vulnerability by THE major adult authority figure in my life; an authority figure whose attention was most often focused on me, and never for benign purpose or positive reinforcement. This final exchange was such a baffling moment I pushed it to nether regions of memory, where it remained, preserved in amber well into the next century.

***

St. Xavier administered mid-term and final exams “college style” (we were told) in randomly assigned classrooms, overseen by randomly selected “proctors” rather than our regular teachers. During junior year, when Nick Plato was my chemistry teacher as well as swimming coach, I finished an exam with time to spare for a much-needed bathroom break. Making my way back to the exam room, I glimpsed Mr. Plato as he performed his proctor duties — in the hallway. Crouching in between an open classroom door and the wall, he peered through the slit, presumably so the test-takers wouldn’t see him. This seemed less bizarre at the time than it does now because, the previous year, I’d taken an exam with Mr. Plato as the proctor where he sat on top of the teacher’s desk, wearing reflector sunglasses so we couldn’t see where, or upon whom, his laser gaze might fall. The man was on a mission, and not just to catch cheaters.

***

Frank Sinatra had nothing on me; I began my senior year at St. Xavier with the high-in-the-sky hopes. After finishing second in the state meet the year before, there was nowhere to go but the top. Any pressure I felt, or exerted on myself, strictly revolved around my performance in the swimming pool. I assumed, wrongly as it turned out, college admission and indeed a full scholarship, would naturally follow a state championship. If I could place first in the 200 yard freestyle, my future would be assured.

***

Over the course of my adult life, I’ve come to view leaders as two distinct types of people. Natural leaders rise to the top, assuming the role organically. They end up leading as opposed to the second type, the aspirational leaders, who plot, plan and connive (if necessary) to place themselves in the pivotal position. Where I fall on this divide is nowhere, or somewhere between. As an adult I’ve mostly functioned as a freelance journalist; independence suits my temperament. But in a group setting, I’ve always regarded myself as a loyal team player, both as a magazine editor and a student athlete.

Being elected team captain wasn’t my top senior-year goal. As the fastest returning swimmer, however, it seemed as though I would be a likely candidate. While I didn’t lobby for the position or assume it was mine by entitlement, I felt ready and willing to accept the challenge if it came my way. It didn’t. A few friends on the team expressed bemusement, or mild outrage but I wasn’t put out, since the elected captain was a good guy. What bugged me were the rumors, muttered but persistent, that Mr. Plato in my absence had instructed the team not to vote for me, presumably for my moral turpitude. I was lax about obeying training rules.

***

Incredibly by current standards, St. Xavier allowed cigarette smoking by juniors and seniors in the basement Student Lounge. During my freshman and sophomore years, the Lounge (as it was known) was the scene of occasional Saturday night dances known as Mixers. Largely attended by a majority of young men from St.X and a minority of young ladies from various Catholic girls schools, from my perspective the Mixers were short on actual mixing and long on “pre-game” partying in the parking lot. In fact, in late 1974, these events were cancelled for precisely that reason.

On weekdays, the Lounge was a refuge not only for smokers but card players and anyone with a free period who didn’t want to sit silently in the library. I frequented the Lounge mostly to play cards and hang out. As far as smoking went, I favored marijuana over tobacco by a large exponent but occasionally bummed a social cigarette here and there. Truth be told, pot (as weed was then known) was clandestinely consumed in the Lounge; a joint would be passed under the table while multiple Marlboros were theatrically puffed in plain sight. I participated in this charade, infrequently.

In addition to keeping his swimming team on the straight and narrow during this hedonistic era, Mr. Plato served as St. X’s self-appointed anti-drug crusader. He regularly patrolled the wooded grounds behind the school in between classes, searching for the stoners (or freaks in Seventies parlance) who would sneak out for illegal refreshment during the day. He secretly monitored the Lounge as well, which I discovered rather too late.

To be honest I don’t remember if we were simultaneously smoking a joint that day or not; it only matters because being caught with marijuana would’ve resulted in expulsion. As it happened, Mr. Plato witnessed me dragging on somebody else’s cigarette and stormed into the Lounge. I forget the precise order of events that followed but by day’s end — January 12 1976 — I was no longer a member of the swimming team.

***

Though the immediate fallout was intense, the damage wasn’t quite as long-lasting as I initially feared. Yet the rest of my senior year chugged along at the tortuous pace of a prison sentence. Relations with my father, who’d always been so proud and supportive of my swimming, deteriorated and didn’t completely recover until 1979, when I started publishing articles in the college newspaper. His disappointment hurt the most.

Obviously, the handful of college athletic scholarships that had been dangled in my direction swiftly and silently disappeared. A well-respected and socially connected St. Xavier alumnus made a fervent and fruitless appeal to Coach Plato on my behalf, I later learned. And while a subsequent, involuntary meeting with the high school’s President — the head Jesuit — didn’t result in my reinstatement either, the latter conversation sprayed lighter fluid onto a flaming barbecue.

Summoned to an austere office in the ominously hushed administrative wing of the high school, I sat down in front of this imposing man— a middle-aged priest I’d barely seen before let alone met — and braced myself for further consequences: suspension or expulsion. Instead, he cut to the chase and explained that in his opinion, my punishment didn’t fit the crime. He wanted to “let me know” that Mr. Plato would be ordered to reinstate me on the team forthwith. My response came as a shock, perhaps to him and certainly to me. Simply put, I urged him not to do it. I had been aware of the rule, and the automatic penalty, and while I agreed that about the severity, I was prepared to abide by the coach’s decision. Creating more controversy was the last thing I wanted. Moving on was my goal. Anyway, I knew Nick Plato well enough to be certain he would never back down. He was a true believer in his own stringent code — a fanatic. About that, I was correct.

Before our chat concluded, I let slip some semi-lurid details about Mr. Plato and his fervent rule-enforcement practices such as recruiting swim team members to spy on each other at parties, etc. The President tried not to raise his eyebrows while pressing for further details, which I provided.

What followed can be only be characterized as a shit show. My dismissal from the swim team turned into a cause celebré during the spring of 1976. Nick Plato announced his resignation — publicly — after a confrontation with his Jesuit superiors about his disciplinary regime, in both the classroom and swimming pool. One fine spring day, a sizable number of upperclassman expressed solidarity with Mr. Plato by staging a mass class walkout. Just like a Sixties protest, only this time in favor of authority.

Another repercussion occurred that knocked me sideways, something I’ve never forgotten, and yet can’t believe ever happened. The Cincinnati Enquirer sports section ran a full page of letters denouncing me as a symbol of “what’s gone wrong with the permissive modern liberal era” and so on. My mind conjures up a full page but can that be true? Maybe it was a half-page, or a handful of letters graphically isolated in a box. Even if in reality it was only a single letter, the effect was deeply mortifying. Not to mention inexplicable. Why would anyone take time out of their busy life to write a letter to the editor about some stupid teenager getting kicked off a sports team for smoking a cigarette? Right or wrong, at that moment I decided — or realized — that my future pointed somewhere beyond Cincinnati, Ohio.

***

I continued swimming for another year because I didn’t know what else to do with myself. Pursuing the sport as a college freshman, somewhat half-heartedly, proved to be instructive in ways nobody could’ve predicted. My parents ponied up for out-of-state tuition at the University of Michigan, for which I’ll always be grateful. I qualified for the varsity team, barely, but never equalled or even came close to my “best times” from high school. Failing in an arena where success had always come fairly easily was both a humbling, and necessary experience. It hurtled me back down to earth. Unlike many scholarship swimmers, I shifted my focus to studying.

Two turning points stand out from my year in the freshman dorm. The first happened on a crisp late autumn afternoon, when I elected to skip the second swimming workout of the day in order to work on a composition for Medieval Studies. Not out of obligation, but desire: I preferred to finish Tristan and Isolde instead of submerging my head in water for two hours.

The second was hearing Patti Smith’s “Gloria” on the campus FM station. Here was a song designed to suit my musical and literary tastes: Beat-inspired poetry fused with surging garage rock and Patti’s immortal tag line, maybe pretentious-sounding to more developed sensibilities but resonant to the very depths of my eighteen-year-old lapsed Catholic soul.

Jesus died for somebody’s sins but not mine

***

Getting kicked off the swim team and the repercussions were formative experiences and also events I purposefully didn’t think about for a long time — most of my adult life. Quite consciously, I didn’t want to credit Nick Plato with wielding any influence on me, even negative. It wasn’t until the #MeToo movement, and sexual abuse scandals of recent years, that I arrived at a melancholy conclusion about my teenage debacle. No doubt I could’ve sexually assaulted one of our female timekeepers — raped an Aqua Maid — and suffered less approbation, less punishment than I did for smoking a cigarette. I hope the same wouldn’t hold true today but I’m not so confident about that. St. Xavier is still an all-male institution.